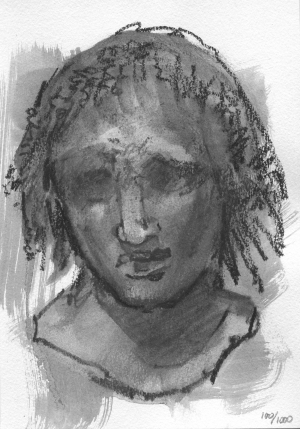

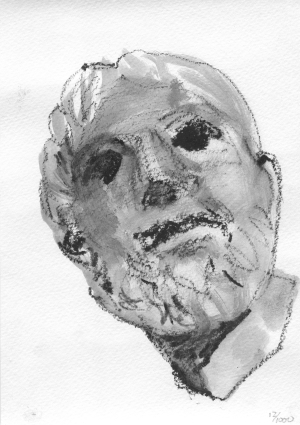

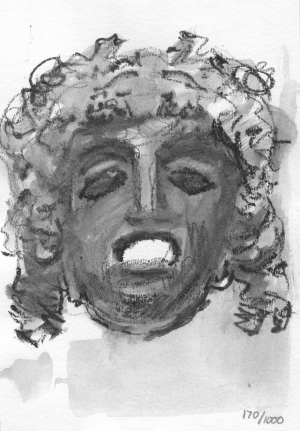

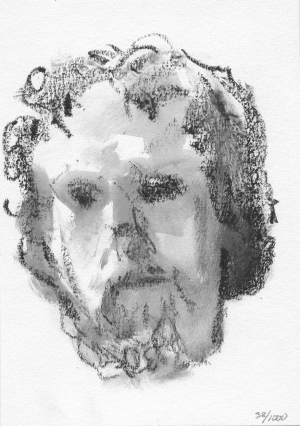

Selections from Meta-Morphic

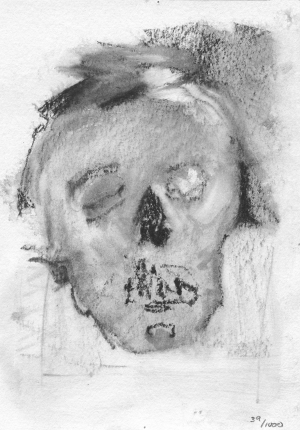

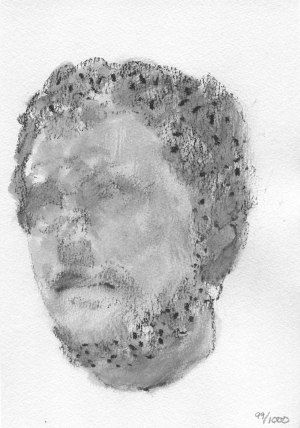

A series of 1000 head drawings in lithographic crayon on paper. Words by Artist David Pettibon

You don’t really know a thing…until you have watched it pass under the sun.

The remnants of a stone head lies half buried in the ground, face up towards the sky. It bears the resemblance of a person, once important, now dead and long forgotten. In the morning, as the sun rises in the northeast, the light cuts shadows across the face, describing the head against the surrounding stones. The low morning light hits the weathered brow in such a way that subtle shadows describe a pensive reflection. In the late morning, those same shadows grow short and the face loses its meditative complexion. Where a beautiful and large nose once protruded, there is a fractured stump, smoothed over by five thousand rainstorms. In the middle of the day, the sun reaches deep into the eye sockets and flecks of light play along the ridges of a faded iris, once crisply carved with care by the favorite apprentice of a master craftsman long dead and forgotten. By the afternoon, the roundness of the eyeballs are perfectly described by crescent shaped shadows cast from overhanging eyelids. By late evening, the stump nose casts a shadow like a worn sundial across tightly closed lips. Perfectly positioned, it is now, in the late evening, when the eye sockets catch the last salmon-colored rays of a heavy, setting sun. For a fleeting moment, the eyes come alive with the warm sunset glow. And then, the head falls flat in the purple twilight. Soon, it will once again become indistinguishable from the surrounding rocks.

You don’t really know a thing- its textures, volumes, protrusions, crevasses, how it takes up space on this planet, its story, until you have watched it pass under the sun. Of course, I wish to suggest the dawning and the extinction (and everything in between) of a thing; a stone head, a civilization, a species but also, I wish to speak, quite literally, of form. I’m talking of the play of light on a set of planes which define the surface of a plump cheek or dimpled chin. The angle of the light to the planes defines how we visually experience the form. This is the stuff that an artist obsesses over. In Michael Sherman’s 1000 Heads, the light that defines each form is translated in deep black marks on the textured, white paper. A smudge ends abruptly into a thumbprint and washes of value cover entire faces like thin lace veils. It is easy to get lost in the marks of any single drawing but don’t stay there. You’ll miss the bigger picture.

Sherman is after something, he knows that the “answer” lies somewhere in the ritual of the process. It would not be an exaggeration to suggest that there is a level of obsession within the artist’s approach to art making. A single drawing, powerful as it is, is not what he is after. It is the ritual that slowly takes shape through the act of drawing, one stone head after another that he seeks. Looking through Sherman’s heads, I am reminded of Morandi’s still lifes; over a thousand quiet oil paintings of the same bottles, simple boxes and vases with flat shadows and a horizon line. Each painting is a masterful study in value and composition. In my head, I imagine (perhaps all too poetically) Morandi, the Italian artist alone in his studio with his still life spread out across a wood table and an easel with a small canvas in the middle of the room. It is 1917 and he is hard at work, dabbing thick blobs of color onto the canvas with an overloaded paintbrush while the rest of world is at war. Similarly, I imagine Sherman hunched over his drawing table in his home in Manhattan. It is late at night and his family is asleep. It is the height of the pandemic and New York City is under lockdown. Under the warm light of a desk lamp, he draws Head Number 170 with a fat litho crayon onto a fresh sheet of paper.